This story was originally posted by the Mises Institute

Dusty Wunderlich | Published January 2, 2023

I first became aware of the Property and Environment Research Center (“PERC”) after moving to Montana and was immediately intrigued by their work. The more I dug into their research the more I realized it aligned with my worldview of free market conservation. The CEO of PERC, Brian Yablonski, was gracious enough to meet with me to discuss more about PERC’s initiatives. Two hours later and we barely touched the surface of PERC’s free-market based conservation initiatives.

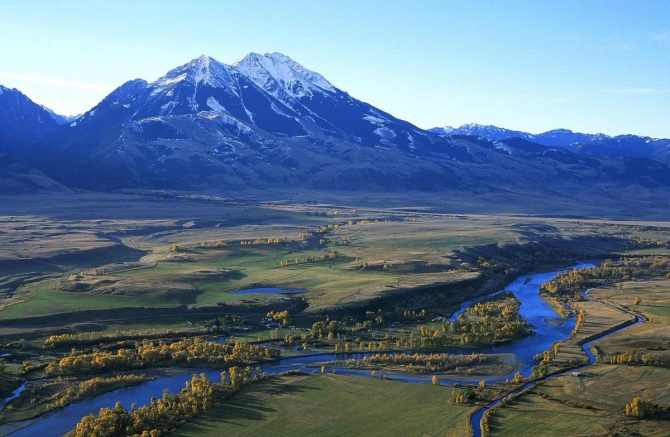

Brian really caught my attention when he told me about a new insurance fund concept they were working on for the ranchers in Paradise Valley. He explained that ranchers in Paradise Valley, the valley directly North of Yellowstone National Park, are having issues with cattle getting Brucellosis from the wintering elk herd. Brucellosis can be financially devastating to a ranching operation and was one of the core issues troubling the ranching community when surveyed by PERC.

The question for PERC became how do we create a free market solution to solve this problem? This is when the Paradise Valley Brucellosis Compensation Fund was created. When Brian outlined the concept to me that would allow for the ranchers cattle and wintering elk to coexist I told him on the spot I wanted to support this innovative solution. In an era of extreme government controlled environmentalism its crucial to illustrate private market solutions for conservation. This is one of those great opportunities to do so!

This is especially important to illustrate when it comes to ranchers and farmers who truly understand the greater natural ecosystem. They are the nations greatest conservationists and stewards of our precious land and resources. There has been an onslaught of attacks on ranchers and farmers from the environmental community, thus, its crucial to illustrate examples of why this community is not at odds with conservation. In fact, their preservation of large areas of land is crucial to maintaining a healthy environmental ecosystem. A task not easily accomplished in a nation that is fixated on urban sprawl.

Simply put, farming, ranching, and conservation are not at odds, and if approached properly, can flourish together. Growing up in a small ranching community I saw first hand the role that ranchers and farmers play in conservation. A role I have seen the government fail at time and time again.

When my wife and I were exploring new places to live what really struck us about Montana was a deeply rooted culture in land preservation. Montana remains home to a multitude of large multi-thousand acre ranches, many that are in conservation easements to ensure they stay that way for years to come. We immediately resonated with this culture and were relieved to see a Western state that was pushing back against uncontrolled growth.

One of the major contributing factors of why we moved from Nevada to Montana was the quality of hunting and fishing. As a hunter and angler, I value healthy populations of wild game and fish. Eating wild game is at the forefront of our families diet. The ability to hunt and procure our own food is extremely important to our family. I want my son to have the same opportunities to hunt and fish as I did growing up. An opportunity I do not think is still viable in Nevada, the state I was born and raised.

Montana boasts some of the most healthy big game, waterfowl, and fish populations in the United States. I believe this to be a testament of the conservation work being done by ranchers and farmers. When comparing Montana to other Western states there is a stark difference in private versus public land.

For example, 80% of Nevada land is owned by a government agency compared to Montana’s 35%. Less public land certainly limits access but I believe it promotes a healthier ecosystem. Privately owned land, specifically large ranches and farms, are managed carefully to drive efficient returns from renewable resources like crops, cattle, and wild game.

In contrast, government run public lands do not have the same incentive nor pricing data which typically leads to misallocating and mismanaging of renewable and natural resources. As a Nevada resident I could not draw a quality tag to hunt and procure food each year for my family. I attribute this to the years of mismanagement of the wild game resources by the government. In Montana, I can buy over the counter tags and hunt throughout the entire state. Thanks to the conservation efforts in Montana, my freezer is full of wild game for my family.

This argument goes at the heart of Mises Economic Calculation problem he penned in his 1920 paper, Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth. A society devoid of market pricing is also devoid of economic calculation (profit/loss) and is bound to misallocate resources. There is no greater example of this than the terrible 20th century food shortages inherent in communist and socialist countries during that time. PERC understands this and is putting actual working case studies to prove this point. Even beyond PERC there are other private organizations in Montana that are rethinking free-market conservation.

One such company I have gotten to know recently is Land Trust. Land Trust was founded in Bozeman and connects landowners with outdoor recreators seeking recreational land access in an easy to use online marketplace. Think AirBnB for the outdoor recreation community. You can go online to book a day of foraging, bird watching, fishing or hunting on a number of private ranches and farms.

The customer experience is remarkable and for the first time we are seeing a true private marketplace for outdoor recreation enthusiasts and landowners. The timing couldn’t be better to help alleviate the pressure between public land advocates and private land owners. Most importantly what will come out of the Land Trust platform is price discovery.

The public land access argument is going to get challenged by this very model, in a positive way. Looking back years from now I am confident that we will have the market data to prove our resources for outdoor recreation access and conservation is better spent in the free market. Quality and access will start to converge thanks to platforms like Land Trust and Funds like the Paradise Valley Brucellosis Compensation Fund.

Organizations like PERC and Land Trust are rethinking how we approach conservation from the free market. A radical concept in a world where the legislation like the Green New Deal is being presented as conservation. This type of reckless legislation puts conservation in the hands of those furthest removed from the environment they are claiming to protect. Even more troubling, is their concept of conservation is based on excess spending without any economic calculation. This flavor of conservation will only lead to further misallocation of resources. Ironically, the very antithesis of conservation.

I am proud to be a Montanan and live alongside the ranchers and farmers protecting this amazing land. I will continue to work alongside groups like PERC and Land Trust to help foster free market conservation so my son will have the same opportunities I had to hunt, fish, and explore untouched wilderness. Something I am unwilling to trust or leave in the hands of the State!

This story was originally posted by the Property and Environment Research Center

Kat Dwyer | Published December 8, 2022

PARADISE VALLEY, Mont. — The Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) is launching an innovative new tool to help ranchers in Montana’s Paradise Valley whose land serves as vital elk habitat. The first of its kind in Montana, the Paradise Valley Brucellosis Compensation Fund will help ease the financial burden ranchers may face if their cattle contract brucellosis from elk in exchange for providing critical habitat for migrating elk. The project brings together a coalition of conservationists, hunters, ranchers, and community members to protect elk migration and open space.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s iconic migrating elk herds depend on working lands for their survival. Thousands of elk descend on Montana’s Paradise Valley every year to feed on ranch lands, where they can spend as much as 80 percent of their time each winter.

But their presence can bring significant costs and challenges to the landowners who provide wintering grounds, including brucellosis, a reproductive disease transmitted from bison and elk to cattle that can have sudden and devastating financial consequences for ranchers. A positive case requires an expensive and lengthy quarantine process in which ranchers often have to isolate their entire herd, undergo testing protocols that can last a year or more, or sometimes even depopulate their entire herd. Until now, private landowners have shouldered the full cost of brucellosis risk.

A market solution for conserving elk and open space

At a time of rapid regional growth and fragmentation as a result of development, supporting large, working cattle ranches by minimizing the impact of brucellosis is an urgent priority for habitat conservation. Many conservationists, hunters, and community members want to protect the region’s vibrant elk herds; the new fund provides a creative market solution for them to support elk migrations and open space.

“There is a significant opportunity for conservationists to privately fund and protect open space that migrating elk depend on in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem,” said PERC CEO Brian Yablonski. “If these ranches were to be carved up and developed, it would be devastating for elk herds and everyone who loves them. The Brucellosis Compensation Fund is a creative market solution that allows conservationists to help reduce a major source of concern for the private stewards of elk habitat.”

For the past several years, PERC has worked with Paradise Valley ranchers to better understand the wildlife challenges they face and develop creative new solutions by applying its research in markets for conservation. Last year, PERC established an Elk Occupancy Agreement in partnership with the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and a ranching family that privately conserved 500 acres of elk winter range.

In a 2019 PERC survey, ranchers identified brucellosis as the most concerning wildlife issue they face. The survey was published in a 2020 PERC report, “Elk in Paradise,” which provided 13 recommendations for conserving elk habitat and working lands in Paradise Valley, including financial incentives such as a brucellosis risk-transfer tool. Since then, PERC has helped organize the Paradise Valley Working Lands Group, and PERC researchers have worked with landowners and other stakeholders to explore potential solutions that would increase tolerance for wildlife by reducing the impact of brucellosis.

“PERC has become a trusted partner in the ranching community of Paradise Valley,” said Druska Kinke, a third-generation cattle rancher in Paradise Valley and a leader of the Paradise Valley Working Lands group. “Their innovative conservation solutions will help working lands continue their goal of habitat stewardship to benefit cattle and wildlife. In addition, PERC and their network of dedicated conservationists are assisting with the difficult issues, participating in the hard conversations, and creating partnerships that will help sustain the working lands of Paradise Valley.”

How it works

PERC’s researchers developed the model in partnership with conservation partners and the ranching community with an aim to keep it as straightforward as possible:

- Timing: The three-year pilot project begins in January 2023

- Participants: Available to any cattle rancher in Paradise Valley, Montana

- Fund size: $100,000 – $150,000 available (currently capitalized at $115,000) to cover 50 to 75 percent of a rancher’s quarantine-related costs following a positive brucellosis test. The partial funding incentivizes ranchers to remain proactive in precautions against the disease.

- Payouts: 75 percent of estimated hay costs, with a maximum payout of 50 percent of the initial fund size for any single quarantine event.

If successful, the fund could be expanded into other areas in the future or lay the groundwork for a more formal financial risk-transfer tool (e.g., a “brucellosis bond”) to address long-term brucellosis risks.

Support from conservation partners

Conservation partners stepped up to fund the program, including financial support from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF), Spruance Foundation, and Credova, an outdoor recreation financial technology company based in Bozeman.

The partners added:

“By sharing the costs that come with providing habitat, this novel approach can increase landowner support for living with wildlife, build trust within the community, and help ensure migration routes and winter range on private lands remain open and avoid subdivision development,” said Greater Yellowstone Coalition Executive Director Scott Christensen. “We are proud to be a partner in supporting a creative new tool for conserving the iconic migratory wildlife of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.”

“Quality habitat is essential to ensuring the future of elk and other wildlife,” said Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation President and CEO Kyle Weaver. “Ranchers play a critical role in this effort. We’re proud to work with them and PERC on an innovative solution to continue to carry out this vital conservation work.”

“The Brucellosis Compensation Fund allows us to directly support our passion for wildlife and the outdoors,” said Credova CEO Dusty Wunderlich. “Growing up in a small ranching community allowed me to see first-hand the role ranchers and farmers play in conservation. Being able to support a private market solution that positively impacts the ranching community and conservation hits at the core of our values as an organization.”

“Private lands and individuals have an important role to play in protecting the abundant wildlife found at Yellowstone National Park and throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem,” said Thomas Spruance, president of the Spruance Foundation. “I’m honored to join other committed conservationists in protecting the region’s majestic elk herds through this innovative approach.”

Thanks for exposing the value large acreage, private property (especially working lands) can lend to conservation of wildlife. Especially on the Paradise Valley floor, private lands that create open spaces and forage for wildlife migration are critical to abundant wildlife, whether for hunting and fishing, or the much bigger economic contributor to our area, namely, wildlife watching (of everything from bison to wolves).

I’m not convinced of (and might just be misunderstanding) your comparison of government owned lands in Nevada versus Montana…as the cause of abundant wildlife here.

If we simply focus in on Paradise Valley (or South Park County, Montana) where I grew up — and the subject of your article — private lands are only about 25% of the acreage (in all of Park County, they represent 45% — but that decreases when backing out non-ag lands). Park County farms as a whole average 1,1400 acres in size, with 159 farms having 1,000 or more acres and 93 of these having more than 2,000 acres. These 93 together had 611,000 acres, about 79 percent of all land in farms, and averaged 6,570 acres in size. Cattle numbered 44,400 in 2012 with 23,000 cattle and calves sold in the year. These cattle operations were on only 211 of the county’s farms and ranches. And, as PCCF has shown, the number of ag properties are decreasing over time. All the more reason, as you pointed out, to do everything we can to make them competitive, viable, and profitable.

So, in our area at least, the percentage of public to private land is more like 75% to 25% (give or take a few basis points depending on how you define south Park County). And, as we all know, wildlife don’t live by boundaries. Indeed, the Northern Elk Herd alone spends a great deal of its time in Yellowstone National Park; consequently, if we included YNP into the equation, the ratio of public to private land further predominantly favors public land. Indeed, the bull:cow ratio is higher in YNP than in Paradise Valley, and we all know where the bigger bulls exist.

Thank you for your post and calling out the importance of private working lands in preserving wildlife populations. I’m not sure the data substantiates your comparison with Nevada. It’s going to take public lands management and private working lands management/incentives to protect those populations…doing so will also protect the $1/2B dollars annual tourism economy in Park County, not to mention our way of life, which includes hunting, fishing, and just plain old enjoying a wild place for the sake of it.

Merry Christmas,

Jeff

Greatly appreciate the comment and data on Paradise Valley. You make a couple important points I would like to address. First, distinguishing working lands versus non-working lands. This is important to understand from a private land conservation perspective and something worth distinguishing on my part in the future. My intent with this post was to illustrate the working private land. Second, as you pointed out, Yellowstone National Park has a significant impact on the natural ecosystem in Paradise Valley. However, I think national parks are certainly an exception when it comes to public lands, due to the resources they garner and how they are managed. We are lucky to have Yellowstone National Park in our backyard for that very reason.

My point on the comparison between Nevada and Montana was to make a general state level comparison between two Western states that have a significant difference in public/private land mix which I think does change how that land is managed at the state level. Large private working land as you pointed out is going to “create open spaces and forage for wildlife migration are critical to abundant wildlife, whether for hunting and fishing, or the much bigger economic contributor to our area, namely, wildlife watching (of everything from bison to wolves).” Nevada’s large working land is limited in comparison which naturally limits the benefits you pointed out above. Government owned land typically falls into non-working land and increased access attributes to more pressure on the ecosystem. I think all are contributing factors to the difference between these two states or any other Western state with similar mixes. I take this position purely from a theoretical viewpoint, specifically deductive, as it would be very difficult to prove this with data since natural ecosystems are much too complex. Having lived in both States now and spending time with ranchers in both states it seems like a logical conclusion but I am always open to refining my position. You certainly gave me some great things to think about and grateful for you reading my post and adding your commentary.

Merry Christmas,

Dusty